ESKD--can be fixed, if...

What is the problem; what should be done; why isn't anything effective being done? AND... how to really solve the kidney shortage

The Problem

Since kidneys were first transplanted in 1954 the demand for kidneys has exceeded supply. An enterprising doctor thought he could act as a broker for kidneys—but some others were repulsed by the thought—and proposed an addition to what became the National Organ Transplantation Act (1984). That part of the NOTA prohibited anyone from obtaining an organ for “valueble consideration1”. The intent was to prevent back alley kidney operations, and to prevent preying on the poor.

NOTA consolidated disparate, chaotic, and inefficient transplant processes nationwide. The Act established a coordinator (Organ Procurement and Transplantion Network—OPTN, which established committees to develop initial procedures published in the Federal Register (the so called “Final Rule”) consistent with NOTA. A pre-existing ad hoc network of transplant centers and computer connections and programs called UNOS (United Network for Organ Sharing) implemented policies to facilitate matching and allocating donated organs from OPO’s (Organ Procurement Organizations) to recipient transplant hospitals 2, —-all under the Health Resources and Services Administration of the federal government. Part of OPTN’s goals is to provide the greatest good to the greatest numbers—while being as fair as possible

Kidneys are the most transplanted organs, and initially kidneys came mostly from deceased “donors” (DD), augmented by a relatively few living donors(LD)—but there were never enough kidneys to satisfy the need.

This shortage remains, in spite of attempts to:

encourage more living donors,

have drivers licensees assign organs for transplant reuse (DD’s),

allowing paired and chain donations3 ;

lowering the standards for usable kidneys (including diseased kidneys);

streamlining wait list and distribution processes,

the transplant wait list is growing. More than half of all transplant candidates die while on dialysis, waiting. And a larger group dies on dialysis, who were never approved to be on the wait list4. The kidney shortage is expected to get worse as the elder fraction of the population continues to get larger5.

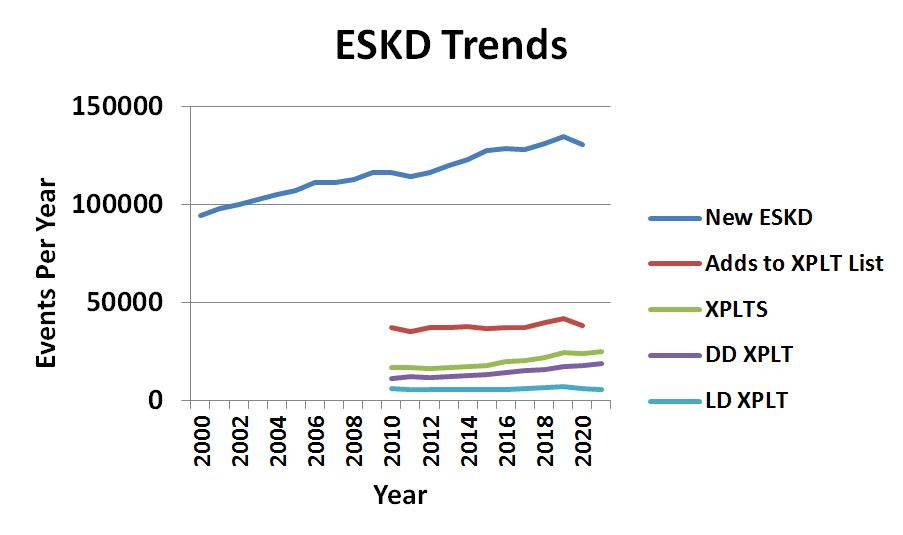

The chart6 above shows in dark blue the number of new ESKD cases per year. That number greatly exceeds the number added to the transplant lists and the disparity is getting worse, implying that: the standards for being on a transplant list are getting harder to meet and that most of the ESKD patients remain on dialysis (and thus die quickly, since dialysis mortality is very high), and that the kidney need is growing rapidly worse.

The red “Adds to XPLT List” line (XPLT means “transplant) is much greater than the actual number number of transplants (green), meaning that even most of those on the transplant list don’t receive a transplant, and they also linger on dialysis until they die, far, far quicker than those who do get a transplant.

The sum of DD (deceased donor) transplants and LD (living donor transplants) adds to total the XPLT line. The deceased donor transplant quantity is growing, but not nearly enough to supply kidneys for those on the transplant list, let alone those ESKD patients that should be on the list.

People in certain states (mostly coastal states), of modest income, and certain minorities die in disproportionately high numbers. The allocation system is inefficient because kidneys spoil in about 36 hours, forcing 25-30% to be thrown away, and others to be given to the closest candidate, not necessarily “fairly”. But all rationing systems suffer from a tradeoff of fairness and efficiency, and most spend an inordinate amount of energy allocating and enforcing, which really doesn’t help the ESKD sufferer.

What should be done

The need for an allocation system, with all its ills, disappears when shortages disappear. After 40 years, we know the much touted methods mentioned above DO NOT WORK. If anything, the kidney shortage has gotten even worse. An obvious solution is instituting a US government program that

pays for living volunteers for kidneys, and pays the estates of the deceased organ donors for kidneys

screens the volunteers to make sure they aren’t coerced and knowingly make a decision to sell a kidney (informed consent)

screens the volunteers and the kidneys extensively to eliminate disease transmission and short lived kidneys

pays for the program from the vast savings from not supporting ESKD patients til they die on very costly dialysis

In this scenario, all of the waiting list, and at least an equal number who never gained admission to the waiting list, would get the best kidneys, lasting 20 years, all perfectly matched to the recipient. The same would be true of the 40K per year that are being put on the waiting list, and a probably larger number that can’t get on the list.

This means we would (very conservatively) gain the following “life years” from all those in the present situation, who won’t get a transplanted kidney:

20 years life x 50K people (from the half of those on the wait list who would never get a kidney)

20 years life x 100K people (from those not on the wait list that should have been)

20 years life x 20K people per year (for the half of the subsequent additions to the list per year that won’t get a kidney)

20 years life x 40K people per year (for future 40K people per year who won’t get on a waiting list)

This totals of 3M life years from eliminating the current waiting list, and 1.2M life years per year in subsequent years, so over, say 20 years (til artificial kidneys are invented, tested, approved, and manufactured in high volumes), totaling about 27M additional high quality life years—not counting additional life years for people who might need a second transplant!

In more detail, a government program could work like this:

For live donors (which are the source of the longest lasting kidneys, and allow better matching) UNOS would solicit donors who believe they meet published govt. qualifications, and offer say, $50K to the successful donor, and a promise to provide a high quality replacement kidney should the donor ever need one. Donors would pay a non-refundable registration fee (to keep people with known problems from applying), and would be extensively tested for kidney function and any health problems. The successful applicants (say 100K of them, initially) would have their antibodies mapped so they can be matched perfectly to recipients when the time comes, and would be placed in a waiting pool. Donors would be screened psychologically to make sure that they were making an informed and reasoned decision. The screening process would take months, allowing donors to change their minds. Recipients, ideally before they are on dialysis, would be scheduled for a transplant in the same hospital as the donor—both of whom would have advance notice. The kidney transfer would occur with no “cold ischemic time”, preserving excellent kidney function. The average life of the live donor kidney would be at least 20 years because of the perfect match, the relatively good health of the recipient, the carefully checked health of the donor, and avoiding “cold ischemic time”. Because the kidney match, having been selected from a very large pool, is nearly perfect, less anti-rejection treatment would be required, protecting the recipient from anti-rejection medicine’s tendency to cause or accelerate cancer.

For deceased donor kidneys (typically from brain dead donors), the successful donor/applicant’s estate would receive a payment based on the kidney quality (as measured by kdpi7). Lower quality kidneys wouldn’t be used, so the average life of the deceased donor kidneys would be much better than the ~10 year life today.

Why isn’t a government sponsored program in place now?

Ever since NOTA, kidney shortages were apparent. Because of section Sec 274e, prohibiting payment for kidneys, improvement strategies as administered by OPTN were limited to:

making improvements to the procurement process (for example, by having drivers elect to donate kidneys on death), streamlining and shortening the prioritizing and distribution process, lowering the quality standards for harvested kidneys), and

attracting live donors through paying incidental fees, and allowing, for example, paired donations.

The added number of kidneys from these changes were modest, and not nearly enough to offset the rapidly growing kidney shortage from growing elderly population and poor heath trends from fast foods and sedentary lives. Though NOTA Sec 274e was really directed at preventing back alley kidney transplants, the letter of the law nevertheless prohibited all financial incentives to the donor. NOTA didn’t consider the possibility of a government monitored incentive program that would remove risks of bad kidneys, and protect disadvantaged groups from being exploited—even though many studies show that such incentives would ultimately be much cheaper than long term dialysis payments—and would save a great many more lives, especially in lower income groups.

There have been only a few small modifications to the Act (adding to a single sentence to Sec 274e) over the last 40 years even though many studies have supported the efficacy of a government monitored program, and have shown that previously voiced concerns would be convincingly addressed.

The reason that nothing has happened is that there is no LOUD, UNIFIED VOICE driving the political agenda to do the obvious: add a few more words in Sec 274e to exempt Federal Programs from prohibition of paying for organs— similar to the one sentence provision previously added to allow paired exchanges.

Effective next steps

Since there are no actual legitimate financial, moral, or effectiveness impediments, the next step is to change policy through alliances with like-minded groups and use political capital to do the obvious. Like-minded groups include the current 500K kidney dialysis and transplant list patients, their families (probably at least another 2M), taxpayers who want to see healthcare money spent more effectively, people who likely will face kidney problems and their families (probably another 20M, lower and middle income, and/or some minority groups), states where transplant lists are long, and medical professionals who are exhausted from telling patients that they have just a few years to live.

Though 2.5 to 20M people are a large number, they are far less than the forces driving other issues, so their influence will have to be well targeted. And there are some influential companies (dialysis companies) with billions to spend8 (and don’t want to see the gravy train end), and a track record of doing so.

A major focus of this substack is to help ESKD patients, their families, and all kidney disease sufferers to SHOUT out to key influencers. More about that in the future.

Have a suggested topic, question, or information you’d like to share? Contact me…

Disclaimer:

The information presented is believed to be accurate, from the author’s experience and research, but it is no substitute for advice from your doctor. The author is NOT a doctor.

On the other hand, doctors aren’t always forthcoming about the probability of success of their strategies, or what might be better alternatives for you. Cross-check with multiple doctors, other ESKD kidney patients, kidney organizations, and this substack.

If you know people who suffer ESKD, or their families, or professionals in the health fields who would be interested in this, please:

In the 1984 NOTA, Sec 274e says:

It shall be unlawful for any person to knowingly acquire, receive, or otherwise transfer any human organ for valuable consideration for use in human transplantation if the transfer affects interstate commerce.

Any person who violates subsection (a) of this section shall be fined not more than $50,000 or imprisoned not more than five years, or both.

For a rough history and explanation of the roles of UNOS, , and OPO’s (Organ Procurement Organization) see History of Transplant Network Organizations

NOTA section 274e today says:

It shall be unlawful for any person to knowingly acquire, receive, or otherwise transfer any human organ for valuable consideration for use in human transplantation if the transfer affects interstate commerce. The preceding sentence does not apply with respect to human organ paired donation.

Any person who violates subsection (a) shall be fined not more than $50,000 or imprisoned not more than five years, or both.

According to NIH , there were 135K new cases of ESKD in 2020, yet there were only about 40K people added to the kidney transplant list. Most of those 135k people would have benefited from a transplant, and will die shortly without one.

A good summary of the kidney problem was written in Atlantic in 2009, and is largely relevant today.

Sources for data: New ESKD patients per year: USRDS data, Fig 1.1; Other data, SRTR Data, Figs: KI-1, KI-64, KI-65

kdpi is a Deceased Donor kidney grading measure that indicates probable kidney life. Life is longer with: younger donors; lower donor body mass index—BMI; absence of hypertension, diabetes, and hepatitis C; lower creatinine; and brain death (as opposed to cardiac death). The best deceased donor kidney life is about 15 years, the worst kidney life is about 6 years, with the majority in the middle, about 10 years.

Dialysis companies revenue in the US totals about $26B, and world wide, about $150 B per year. They haven’t been shy using that money to influence government policy. For example, they spent $110M in 2018 defeating a referendum in California which would limit dialysis companies profit to 10%. See this CA 2018 referendum description. The referendum failed by a large margin, defeating the SEIU (union sponsored opposition) who could spend only $18M

Also see another dialysis company abuse in conjunction with American Kidney Fund in this article from Scientific American: Kidney Dialysis is a Booming Business—Is it Also a Rigged One?

Even purported dialysis support “foundations” such as the National Kidney Foundation are known to accept up to 40% of their annual spending from “corporate sponsors” (who are actually undisclosed), which might well include dialysis companies—and cloud NKF’s judgment.